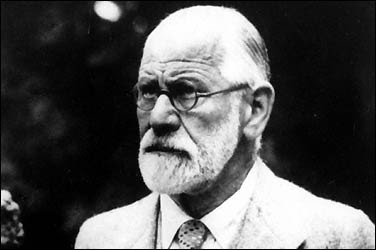

In the selection “Medusa’s Head,” psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud fleshes out his interpretation of the mythological image as a deep-seated sexual issue, stemming from the human fear of their mother’s genitals devouring their own. In his analysis of the metaphorical representation of female genitalia, Freud sheds light onto the paradox of heterosexual male desire – a force which is both terrifying and undeniably attractive. Despite the comical effects and his persuasive argumentation, Freud’s assertions ultimately fail to explain the complexities of human sexual relations, as they gravitate around an ignorant male view of women’s sexuality.

For Freud, sex is attached to an unspoken, irrational fear of castration, where the vagina represents a vortex of simultaneous pleasure and horror. In the style of third person narrative, Freud creates a situation where the “other” is identified – in this case, the body of the female, represented by Medusa’s decapitated head is the center of alterity through the mystification of female sensuality. Instead of exploring the idea of its multiple possibilities, Freud articulates one, monolithic, uniform kind of female sexuality. From this position, Freud is failing to substantiate his arguments, as they are clearly seen to stem from impossible fears, and a blatant lack of understanding the fairer sex.

Mystifying the organs of female sexuality have both an amusing and a maddening effect – Freud attaches the fear of castration in sex to a boy’s glimpse of his own mother’s vagina. Yet where does this fear originate? Freud lacks an explanation for how anyone would even associate sexual pleasure with the possibility of losing one’s penis. Perhaps the most absurd tenet of his interpretation of Medusa is the idea that the snakes in her hair are “a confirmation of of the technical rule according to which a multiplication of penis symbols signifies castration.” The only technical rule which could be applied to Freud’s argumentation is that he defies every epistemological convention.

In short, Freud lacks understanding in the issue of sex – particularly of the female persuasion. However, his interpretation of the myth of Medusa and her sexual evaluations brings another, more philosophical issue to the surface. It is the displacement of social values which creates a dichotomy of sensuality: the ignorance towards the female body and its responses to sexual desire in turn becomes a symbol of both desire and fear, and even possibly hatred. According to Freud, the sight of Medusa’s head (and therefore the sapphic images associated with it) makes the man “stiff with terror…” yet at the same time “offers consolations… he is still in possession of a penis, and the stiffening reassures him of the fact.” This line is particularly absurd, since the spectator has an erection, how could he have ever feared for the loss of his member?

Ergo, Freud’s exploration of female sexuality through the literal and figurative interpretations of power in the myth of Medusa creates more ignorance on the topic instead of clarifying it. Even in this short selection, an envious, fearful misogyny resonates in this analysis. It is perhaps due to the social repression of women at this time in history that causes them to be “othered” to the point of being recognized as either a symbol of sexual desire, fear of castration, or both.